Varnish Procedure; Part Three

Antiquing

Well– as I said in an earlier post, one of the decisions that has to be made is whether to “antique” a new instrument. As a rule, I try to go easy on this, doing minimal shading and light wear patterns; but it really does pay to do something to satisfactorily darken the bare wood before beginning varnishing. Otherwise, I will regret it later on, when I can see the bright wood through the dark varnish, and there isn’t much I can do to make it look right.

As you may recall from the first post on varnishing this violin, I was not very happy with that first coat of varnish–it was too light in color. I should have stripped it off and started over, but I kept thinking “just a little more varnish!” Well…it wasn’t working. Especially under bright light, the light wood just grinned at me from behind the varnish.

So, not really wanting to strip it and start over, I used a different ploy: I coated the entire instrument (except the handle area of the neck) with a very dark pigment, allowed it all to dry, and then sanded it back off, knowing that I would damage my lovely varnish in the process, but also knowing that the dark pigment would only remain in the low areas of the grain, and that, if I was careful, there would still be a fair amount of the varnish left, but with bits of the dark pigment remaining, looking like the accumulated dirt and skin-oils from hands, ground into the wood over the years….hopefully.

And, it seems to have worked. That foundation looked a little better…more believable, I suppose; so I went with it, and here are the results:

I am not showing the intermediate steps…they really put the “ugh” in ugly, for about a day or two, there. But after the pigment was sanded back off, and the varnish cleaned up; using a rag, I rubbed a seal-coat of very light spirit varnish into the whole fiddle, to lock down the pigment and clean off any loose stuff left from the sanding off of the pigment. Then I began re-varnishing with the dark red-brown varnish, thinning with alcohol as needed, to get it to flow well. It took a couple of days to get it to a point I felt happy with, but I am much more satisfied with it now than before. I’m sure some will disagree and hate it, but: sorry, that is the way this one had to go. Perhaps the next one I will try something a bit different, and get it right the first time.

Rationale Behind “Antiquing”

Meanwhile, here is something to consider, regarding “antiquing”: I had a professional violinist (Adam LaMotte) tell me, “Chet, we players all want an old master violin. If we can’t afford one, then we want our violin to look like an old violin.” A famous violin-shop owner in England (Charles Beare) put it this way: “An unattractive violin simply does not get played…it gets no attention from customers. There is absolutely no reason you should consider ‘antiquing’ your instruments, unless, of course, you actually want them to sell!” That is fairly succinct. Evidently even the “big boys” recognize this odd little fluke in the violin market. I have never understood the market trends that drive people to buy pre-distressed (worn-out) blue-jeans, either, but someone has made a lot of money doing just that.

Ah, well…at least the “wear” on the violins usually does not hurt them at all. (Although I have known of people deliberately cracking and re-gluing instruments, and it is fairly common to bush and re-drill peg-holes on a brand new fiddle, to make it look old. And some go as far as a scroll-graft, knowing that virtually all pre-1850 violins have had a neck-graft, and a genuine neck graft is usually a sign of a genuine old violin. Sigh… not anymore. I have done neck-grafts, but only when there was a cause, and it was a needed repair. Same for peg-bushing. I have done lots of them, but only in repairing old instruments.)

So– the bottom line, to me, is that I really like them to look at least a little like an old, gently worn violin. And sometimes even, a very old, heavily worn violin. (This one fits into the latter category, except no cracks, and no bushed peg-holes.) There are certainly people who won’t like it…but there will definitely be those who fall in love with it, too, so I’m not too worried. There are better ways to darken the wood without hurting it, though, and next time I will try to do so. (Some people have tried certain chemical treatments which looked remarkably good, but, as it turned out, destroyed the structural integrity of the wood.)

Saddle

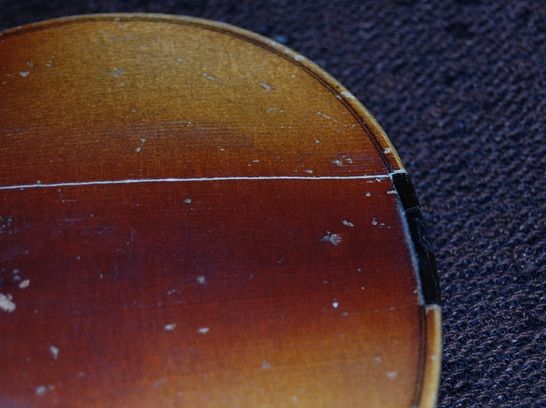

You will also notice that the saddle has been installed. This is another thing I do a little differently: I round the corners of the saddle, thus eliminating the stress-risers built into square mortises.

Why Rounded Corners?

Ever notice the shape of the windows in airliners? Ever wonder why they haven’t any square corners? (See Comet Disaster) Here’s a partial quote: “In addition, it was discovered that the stresses around pressure cabin apertures were considerably higher than had been anticipated, especially around sharp-cornered cut-outs, such as windows. As a result, future jet airliners would feature windows with rounded corners, the curve eliminating a stress concentration. This was a noticeable distinguishing feature of all later models of the Comet“

At any rate… the intent of the rounded corners is to prevent saddle cracks.

So far, my practice of rounded saddle corners has proven quite successful. Also, though you can’t tell it from the photos, there is a tiny gap at the ends, to allow for plate expansion and/or contraction. It isn’t much, but it is there.

Fittings

The saddle is ebony, as will be the fingerboard, nut and tuning pegs on this violin. I haven’t decided yet whether to use an ebony tailpiece and chin-rest, but I probably will do so. (Tradition, you know….) 🙂

The next post will complete the set-up procedure.

Thanks for looking.

Follow

Follow