Five String Report: Adding Fittings

End pin

I failed to take any photos of this, but– it is pretty simple: I centered a hole on the center joint between the lower ribs, and centered between the plates. I drilled it first to 1/8″, then to 7/32″, and finally reamed it with a 1:30 tapered reamer… the same one I use for tuning pegs. I shaved the endpin blank to the correct size and taper using my peg-shaper, while gripping the endpin with a special homemade gripper. I shaved the endpin until it would just barely fit into the hole, leaving a little clearance between the collar and the rib surface. (There is a photo of it later on…)

Fingerboard:

In the photo below you can see some of the tools I used to fit the ebony fittings to the violin. Looking at the fingerboard, you can see the three “dots” of glue that secured it to the neck while I was shaping both the neck and the fingerboard. When I re-install the fingerboard, there will be glue on the whole faying surface. The carved out portion will help to lighten the fingerboard, and apparently helps tone.

The black mechanism is the peg shaver I use. The block next to it is the gripper I use for end-pins. The endpin blank is right next to the shaper. The small ebony block between the shaper and fingerboard is the nut blank. The larger ebony block midway along the fingerboard is the saddle blank. The fingerboard has the shape laid out that I intend to carve away, and the gouges and scrapers on the right are the tools with which I did it.

So, one of the first things I did was to make sure my tools were sharp, then I went all around the edges of that trough shape, carving away small chips of ebony to produce a shallow trench all around the edge. Then I carved as best I could with the gouges, until I decided it was time to get the planes into the fight. The little Ibex plane worked well, but the little wooden homemade plane actually worked better, because it has a deeper curve in the sole. It was made of a small section of a broken hammer handle, a piece of scraper blade, and a threaded steel plate to adjust tension and hold the blade in place.

Saddle

Next I worked on the saddle: I cut my saddles with radiused front edges, so as to avoid saddle cracks, which are extrmely common in violin-family instruments…partly, I am convinced, because virtually everyone makes them with square corners, which adds a huge stress-riser to that location in the spruce. To me, that is asking for a crack. I try to avoid suich things.

Some luthiers try to avoid cracks by leaving a small gap on the ends…that makes good sense, too, but why not eliminate the “notch” altogether? Just my opinion…. Either way, you have to remove the wood of the violin front plate to receive the ebony saddle. I use a thin knife to slice through the spruce, and then a flat chisel to loosen the piece being removed. I set aside the piece in case it turns out I made an error of some kind, and need to put some back. It is a whole lot easier to match grain from the piece you just removed, rather than from some random piece of spruce.

Once the saddle fits the mortise perfectly, leaving a small gap on each end (about the thickness of a business card), I glue the saddle in place, and forget about it. Here is a photo of the finished saddle. I didn’t take photos while I was carving. I get pretty wrapped up in what I am doing and forget to take pictures.

Pegs

The next issue was the pegs. I wanted them done before I installed the fingerboard, simply because I wanted to be able to set the instrument aside so that the glue under the fingerboard could dry, and not feel that I was being prevented from working.

I had earlier drilled pilot holes in the pegbox, so that I would have guides to help keep the holes perpendicular to the centerline. So I reamed out those holes, all to approximately the same size, using the same reamer (1:30 taper) as I used for the endpin.

Then I sliced a shallow groove next to the collar, on each peg, all the way around, using a very fine razor-saw, to avoid breaking off the collar. (Doesn’t always work, but it seems to help.) I shaved the pegs until they fit the holes, at nearly the right depth, then “greased ’em up” with peg dope, and worked them in, so that the holes and pegs fit perfectly. Later I trimmed off the excess length of each peg on the far side of the pegbox, domed and polished the cut ends, so they would look nice, and put the pegs back in place.

Fingerboard Installation

Last, I installed the fingerboard…I had marked ahead of time the exact location where the nut and fingerboard were to meet; so now, all I have to do is put the fingerboard exactly where it was before (against that line) and glue it in place. I positioned it using a single spring clamp and aligned the upper end as closely as I could, then aligned the lower end as well, and added a large spring clamp in that location. Finally, I re-adjusted the upper and lower clamps until both ends were perfect.

Then I removed the lower clamp, and, using a thin palette knife, I ladled hot hide glue into the space between the neck and fingerboard, sliding the blade up the neck as far as it would comfortably go, and replaced that clamp so that it squeezed out hot hide glue all around. I cleaned up the excess quickly, and double checked to make sure that the position was again perfect.

Then I removed the upper clamp, and repeated the gluing routine, but this time, as I cleaned up, I kept adding more clamps, removing a previous one, and wiping carefully, until I had four clamps in place and no glue drops where they did not belong.

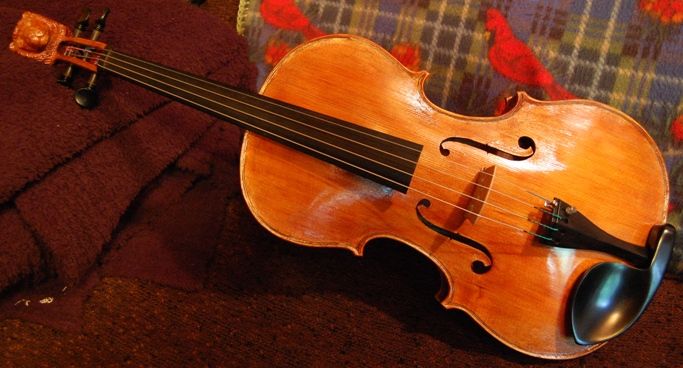

That was pretty much the end of the day. My hands were tired and hurting, and I had other things that needed to be done. Much later, I got back and removed the clamps:

The nut will have to wait until the fingerboard has been planed and scraped to exactly the right curvature, and polished smooth. We call that “dressing” the fingerboard.

After that it will be “set-up” time.

My next post will show the finished fiddle, strings and all.

Thanks for looking.

Follow

Follow